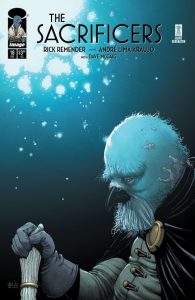

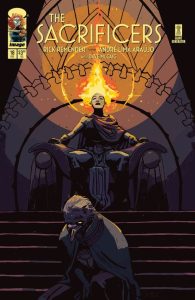

The Sacrificers #18, by Image Comics on 12/17/25, asks whether revolution and desperation can coexist, or whether survival always demands a terrible compromise in the wreckage of broken promises.

Credits:

- Writer: Rick Remender

- Artist: Andre Lima Araujo

- Colorist: Dave McCaig

- Letterer: Rus Wooton

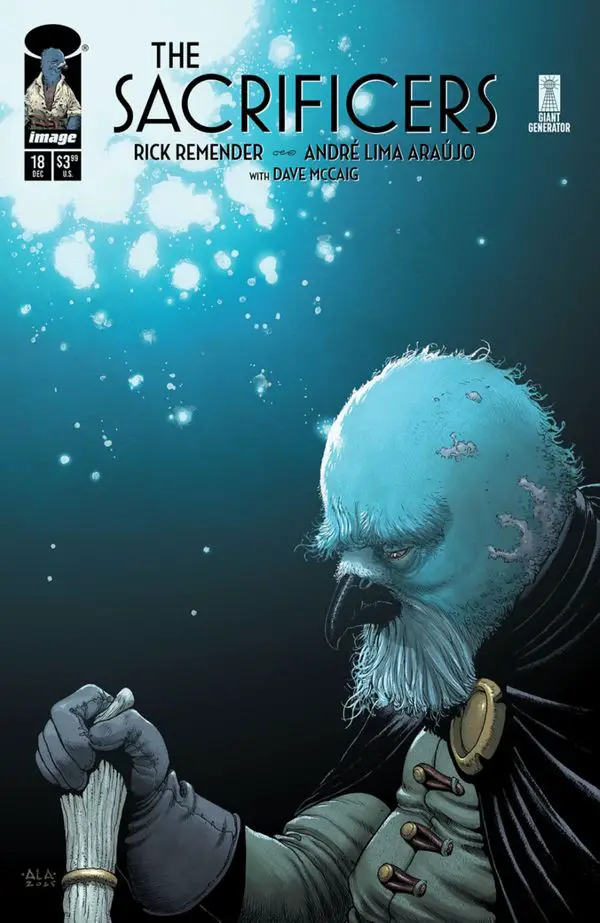

- Cover Artist: Andre Lima Araujo, Dave McCaig (cover A)

- Publisher: Image Comics

- Release Date: December 17, 2025

- Comic Rating: Teen

- Cover Price: $3.99

- Page Count: 32

- Format: Single Issue

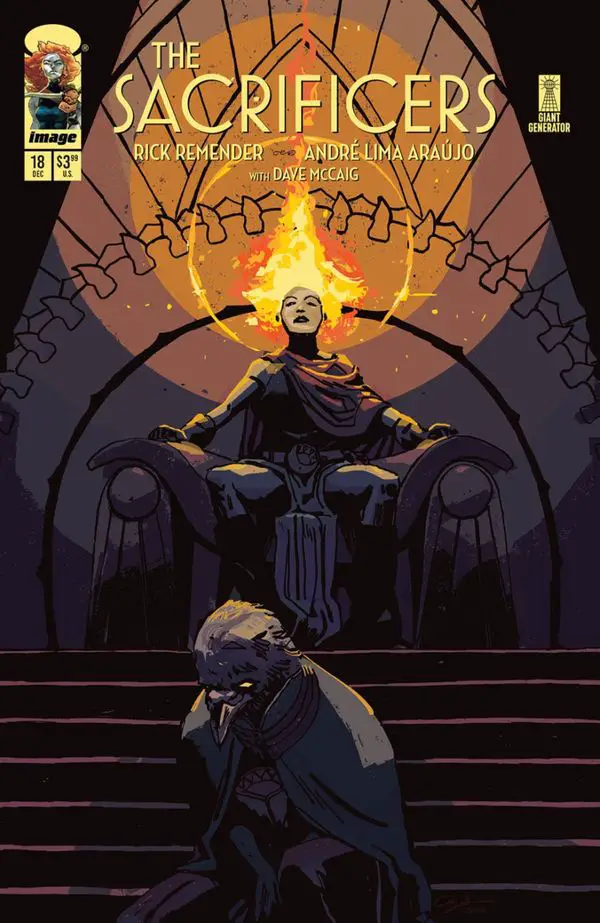

Covers:

Analysis of THE SACRIFICERS #18:

First Impressions:

The opening punches you in the gut with raw suffering, shifting between a mother struggling to keep her son alive while a mythic system crumbles around her, and Soluna breaking under the weight of becoming a god in everything but name. That immediate collision between intimate loss and apocalyptic scale hits hard, and the concept executes by making every page feel like watching a dam hold back water that has already turned to poison.

Recap:

In The Sacrificers #17, Soluna returned to a harrowed royal house one year after the violence had ended. She was welcomed by gods and royals through brittle ceremony, then faced her father Rokos, whose scorched reign demanded public renewal and placed Soluna as the figurehead of a ceremonial sacrifice meant to fix their broken world. In the high hall, Soluna exposed the ritual as poison rather than blessing, refusing to drink the cup and upending the entire order that demanded children die for the realm’s survival. She declared revolution and an end to the reign of divine cruelty, and the foundation of Harlos burned as the age of living was supposed to begin anew.

Plot Analysis:

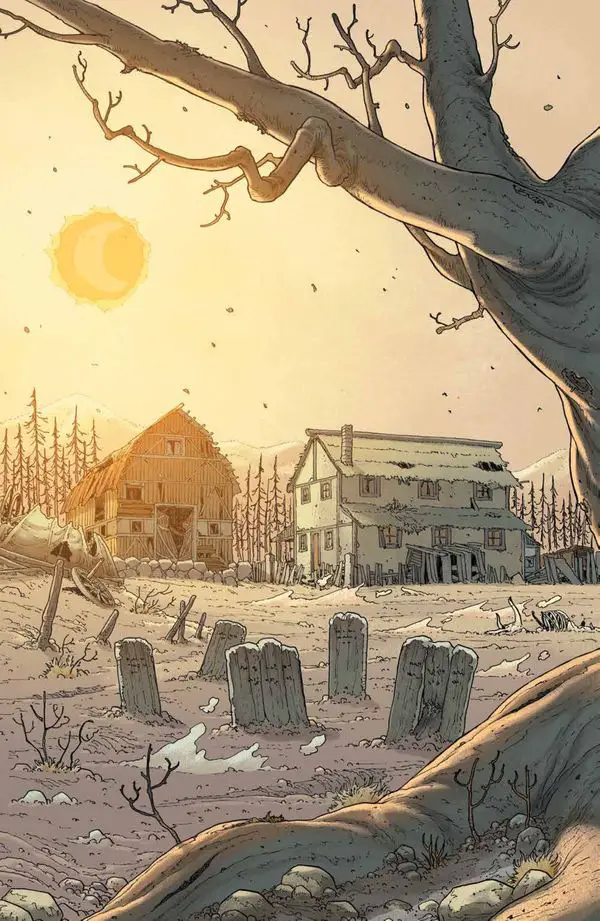

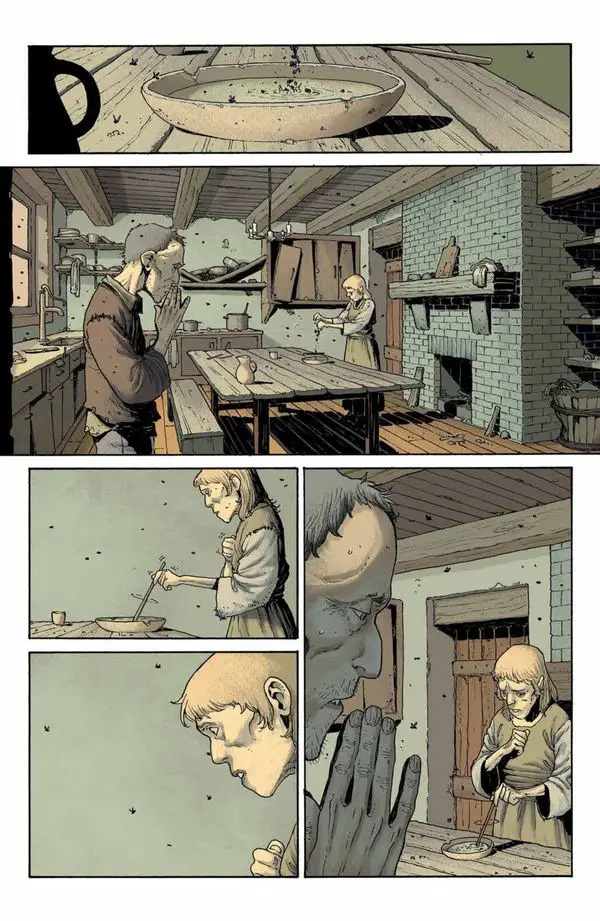

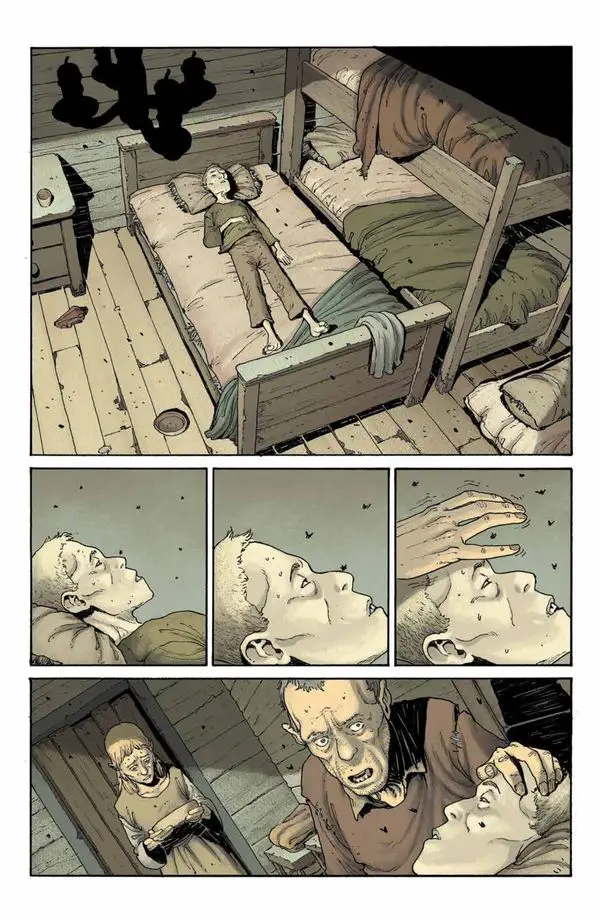

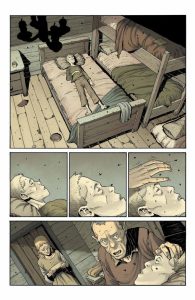

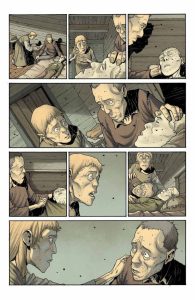

Thirty years have passed since the end of that uprising, and the world Soluna promised to build has become something else entirely. A father carries his sick son through crowded streets, desperate and frantic, seeking help from Soluna, the Last Mother of Light. The child burns with fever as the father begs and struggles through overwhelming crowds, but despite everyone’s efforts, the boy dies in Soluna’s care. The parents are devastated, the father screaming at the void of what kind of god allows such suffering to continue, over and over again.

Meanwhile, Soluna at home with her own family reveals the true cost of her promise to be the world’s replacement for the missing gods. She’s tethered to mechanical systems, giving her body as a literal moon and sun to regulate the planet itself. Her husband Pigeon must coax and beg her to continue, reminding her that if she stops giving light, crops fail, forests crumble, and everything they’ve sacrificed for will collapse to nothing. She’s so exhausted she can barely move, and Pigeon keeps asking for just a little longer, always a little longer.

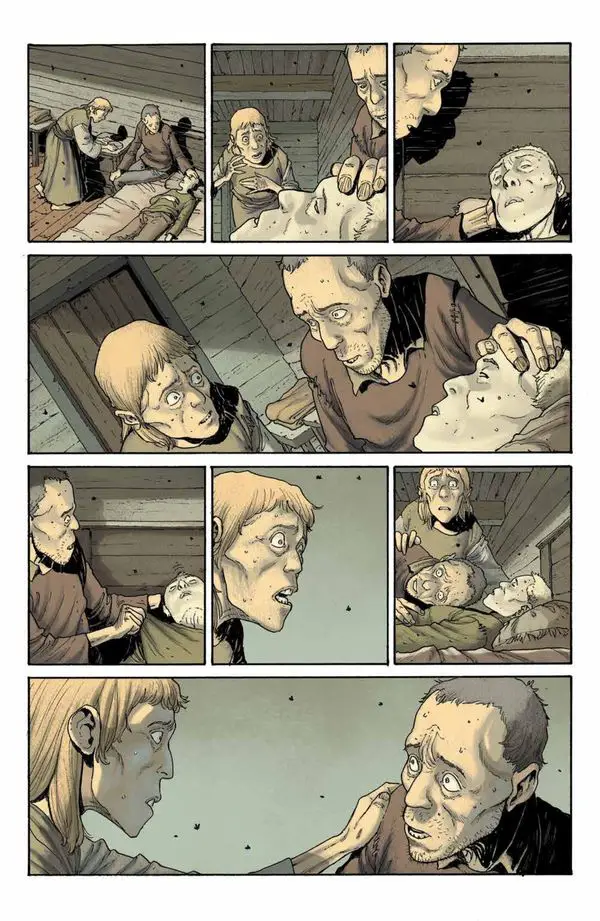

Beatrice, Soluna’s sister, arrives at the house carrying terrible news and worse judgment. She tells Soluna plainly that her grand solution hasn’t worked; the people suffer, sickness spreads, crops have died, and plague is everywhere. When Soluna insists everything is under control and nearly complete with new machines arriving from the Emperor, Beatrice becomes desperate, suggesting that Soluna’s own sons, Soll and Losl, have the power of the old gods in their veins and could help carry the burden. Soluna refuses absolutely, declaring that her sons will never suffer as she has suffered, that she has given her entire life to spare them from this servitude.

The issue ends on the deepest crack in Soluna’s foundation. Beatrice points out the brutal truth: under Soluna’s rule, children don’t get stolen for one altar anymore. Instead, they all suffer under the weight of a world that demands constant sacrifice and receives constant desperation and death in return. The revolutionary has become the tyrant, and she may not even realize it yet.

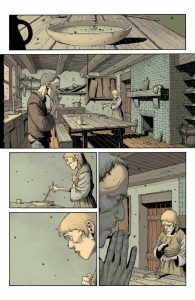

Story

Remender crafts a structure that mirrors the series’ core tension: personal anguish layered against systemic collapse. The pacing deliberates between quick, punchy moments of dialogue and longer panels of quiet suffering, using rhythm to heighten the emotional impact. The opening hospital sequence moves with almost documentary precision, showing the helplessness of parents and healers in real time. Later, conversations between Soluna and Pigeon crackle with the kind of dialogue where every word carries weight, where “just a little longer” becomes a haunting refrain that means everything is ending. Exposition integrates cleanly without ever feeling forced. The dialogue between Beatrice and Soluna is sharp and unflinching, each accusation landing because it’s built on observable facts from the panels themselves. Readers can see the systems breaking down, so when Beatrice names them, it resonates.

Art

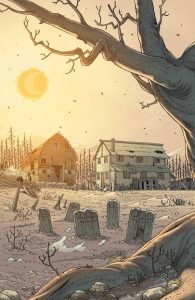

André Lima Araújo and Dave McCaig deliver visual storytelling that makes the emotional weight visible. The opening hospital pages are composed to maximize claustrophobia and desperation: tight panels showing hands, faces streaked with sweat, the overwhelming sense of too many people in too small a space. When the focus shifts to Soluna’s home, the composition opens up, but the backgrounds are laced with mechanical systems, cooling tubes, and equipment that frames her not as a queen but as a prisoner. McCaig’s color work is devastating: the hospital scenes wash in sickly grays and greens, suggesting illness and decay. When we see Soluna’s body tethered to machinery, the light becomes almost beautiful but wrong, like looking at something sacred that’s been broken and repurposed. The contrast between warm candlelit interiors and the cold machinery creates a visual language that says: comfort and function are in direct opposition now.

Characters

Every character here moves according to internal logic forged in trauma. Pigeon, revealed to be the father who lost his son at the comic’s start, now faces the same impossible choice his old world demanded of others: continue the system or watch everything collapse. His consistency is painful to watch because readers have seen him suffer before, and now he perpetuates suffering himself, not out of cruelty but necessity. Soluna’s motivation is locked between maternal protection and national obligation, and both are destroying her from different directions. She refuses to sacrifice her sons because she knows exactly what that costs, but her refusal to let them help means their world continues to poison itself.

Beatrice arrives as the voice of hard truth, and her motivation to push Soluna toward using her sons shows she’s not malicious but desperate enough to suggest the unspeakable. The father carrying his sick son is unnamed but potent; his cry of anguish at the end has no artifice because it comes from a specific person experiencing a specific loss. Relatability works here because these aren’t mythic archetypes making abstract decisions; they’re parents making impossible choices with real blood on the consequences.

Originality & Concept Execution

The series promised to explore what happens after revolution, and this issue delivers that by showing that replacing a corrupt system with a better one doesn’t erase the cost of systems themselves. The concept of “It Will Always Be the Same” Part 3 of 6 lands hard here: Soluna swore to end sacrifice, but she’s become the sacrifice. The originality lies in refusing the typical arc where the hero’s solution is vindicated; instead, Remender shows how even good intentions can create new forms of suffering. The execution succeeds because it’s built on visual evidence. Readers see the father losing his son, see Soluna’s exhaustion, see the mechanical systems, see the plague marks on the people begging for help. This isn’t philosophical musing; it’s showing a broken promise through concrete images. The premise holds because the comic trusts the reader to understand the tragedy without narration explaining it.

Positives

The comic excels at depicting systemic failure through personal moments. The opening hospital sequence ranks among the most emotionally punishing scenes in the series; it achieves devastation not through shock value but through specificity. Every person in that crowd has a desperate reason to be there, and McCaig’s colors make their desperation visible. The visual design of Soluna’s mechanical systems is brilliant, transforming a queen’s chamber into a life-support unit and making her literal the figurative notion that leaders sacrifice themselves for their people. Beatrice’s speech arrives as the emotional and intellectual climax, and Araújo frames it with tight close-ups that make her accusations feel personal and precise. The restoration of Pigeon as a tragic figure is handled with care; readers understand why he keeps asking Soluna for more without ever feeling like he’s a villain for doing so. The pacing never lets the mood deflate; even quiet moments carry tension because the underlying question never changes: how long can this continue?

Negatives

The issue risks losing younger readers with the density of emotional weight; there’s almost no moment of levity or reprieve, which can make the read feel relentless. Some may find the lack of external action (this is a dialogue-heavy, internally focused issue) to be slow or even static compared to earlier chapters. The resolution of the opening hospital sequence, while devastating, might leave some readers feeling manipulated by its emotional precision; the father’s cry of anguish is so designed to hurt that it borders on calculated.

The ending, while thematically perfect, leaves Soluna’s response uncertain. Readers don’t see what she thinks or feels when Beatrice speaks, which means the issue closes on a cliffhanger of emotional state rather than plot action. For some, this will feel like an incomplete thought. The broader problem the story poses, about systems and sacrifice, is philosophical rather than plot-driven, so readers seeking a clear conflict or antagonist to rally against won’t find one here.

Art Samples:

The Scorecard:

Writing Quality (Clarity and Pacing): [3.5/4]

Art Quality (Execution and Synergy): [4/4]

Value (Originality and Entertainment): [1.5/2]

Final Thoughts:

(Click this link 👇 to order this comic)

THE SACRIFICERS #18 asks you to sit in discomfort and watch a good person discover she’s become the machine she meant to destroy. There are no villains here, no easy targets, just people making impossible choices in a world that punishes decency as readily as cruelty. If you want a comic that feeds your brain while it breaks your heart, that uses visual storytelling to explore why systems persist even when they’re corrupt, then this issue earns the price of entry. But if you’re looking for a fun break or a hero’s triumph, you’re reading the wrong book. This comic isn’t interested in making you feel good; it’s interested in making you understand, which is harder and more important.

We hope you found this article interesting. Come back for more reviews, previews, and opinions on comics, and don’t forget to follow us on social media:

If you’re interested in this creator’s works, remember to let your Local Comic Shop know to find more of their work for you. They would appreciate the call, and so would we.

Click here to find your Local Comic Shop: www.ComicShopLocator.com

As an Amazon Associate, we earn revenue from qualifying purchases to help fund this site. Links to Blu-Rays, DVDs, Books, Movies, and more contained in this article are affiliate links. Please consider purchasing if you find something interesting, and thank you for your support.