It’s not Character, Motivation, or Goals. It’s the C-word.

I listen to a lot of podcasts about comics and the comic industry. Some might say too many.

In a recent podcast (names scrubbed to protect the innocent), one of the co-hosts recalled a talk he was giving to comics writers and editors about the basics of storytelling and what every story must contain. The short explanation was that every story must have a Character with a Motivated Goal that goes on a Journey.

An Incomplete Definition

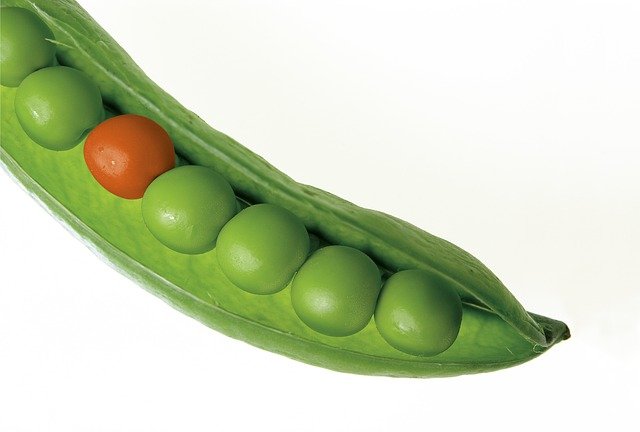

The more I thought about that definition, the less it sat well. It dawned on me that while that definition fit every story one might read, it was missing a key element that makes a story a story instead of a simple description. Here’s an illustration:

Joe wants to go to the store to get milk so his kids will have milk for their cereal in the morning. He gets in his car, drives to the store, and walks back to the refrigerator aisle. Joe picks up a gallon of milk, pays for it at the front register, and drives home.

–The End—

What you’ve just read fits perfectly into the co-hosts definition. We have a Character (Joe) with a Motivated Goal (get milk for his kids) who goes on a Journey (drives to the market, gets the milk, and comes back). Yes, it is a story in the grammatical sense, but realistically, it’s a described event.

The Missing Ingredient

Now, let’s add in the missing ingredient and see how it changes things.

Joe wants to go to the store to get milk so his kids will have milk for their cereal in the morning. He gets in his car, drives to the store, and walks back to the refrigerator aisle. Joe picks up a gallon of milk when suddenly…

An armed robber fires his pistol near the entrance and demands everyone put their wallets in his bag. Joe is too far back in the store to be noticed, so he dives into an open closet in the hope he won’t be noticed. Eventually, the robber leaves. When the police arrive to take statements, Joe describes what happened. He then pays for his milk at the front register and drives home.

–The End–

Besides the obvious excitement, the missing ingredient to our unnamed co-host’s definition is the C-word: Conflict

Conflict IS the Story

To put a fine point on it, if there is no conflict, there is no story worth telling. It’s the essential ingredient because a journey that doesn’t involve change is little more than running an errand, and Conflict is the catalyst for change.

Let’s update the formula.

A story is a Character with a Motivated Goal that goes on a Journey and encounters Conflict along the way.

Structurally, a Conflict is that thing or event that interferes with the Character’s journey in three key ways. Let’s stay on Joe’s quest for milk and explore different ways it could have played out.

Conflict Forces the Character to Change

Joe sees the robber and decides to hide in an open closet until the robber leaves. The robber’s appearance forces Joe to take action. In this case, a conceivably cowardly action based on fear.

Joe’s a human being with emotions and thoughts like everyone else, so this unusual robbery and his less-than-noble response shakes him up. Perhaps he regrets his cowardice. Perhaps he experiences some form of traumatic stress nightmare for days or weeks later. Or perhaps his regret over how he handled the conflict inspires him to take some confidence-building self-defense training.

There are plenty of possibilities. But the key is a Conflict that interferes with Joe’s Journey forces him to overcome the Conflict. The act of overcoming changes him.

What’s more interesting for a reader? Joe getting a gallon of milk or the aftermath of Joe’s traumatic experience while getting the milk?

Conflict Forces Everything to Change Around the Character

In an alternate form of storytelling, the Character may not change by the introduction of Conflict, but the environment or characters around him will. Remember, without Conflict, there is no change. Without change, there is no story. Let’s take another run at Joe’s story.

Joe sees the robber and decides to do nothing. He simply stands there with a look of indifference on his face, possibly because the store is in a rough neighborhood and robberies are a common occurrence.

The robber sees Joe is not taking out his wallet, so he rushes Joe with his gun raised. During his run, the robber slips on a wet patch and knocks himself unconscious when his head hits a nearby shelf. Joe calmly steps over the unconscious body and drives home after paying for his milk.

Joe seems unphased, but the media reports pronounce Joe to be some kind of hero under pressure. He’s soon lavished with praise and accolades from his family, friends, and community.

— The End —

In this version, the main Character was confronted with a conflict in his Journey, but overcoming the Conflict didn’t change anything about the Character. It changed everything around him.

Again, the Journey to purchase milk is not the story. The story is about how everything in Joe’s life changed when the Conflict was resolved.

Conflict Changes the Goal

Sometimes the wall is just too big to go over, around, or through. Let’s take one more crack at Joe’s milk saga.

Joe sees the robber and decides that the best course of action is to go for a hard tackle. He sprints headfirst into the robber’s midsection but not before the robber gets a shot off, hitting Joe in the shoulder. The robber is down and restrained by some of the other customers, and Joe is bleeding out. The next few days are a touch-and-go fight for Joe to survive in the hospital.

— The End —

In this example, the Character (Joe) with a Motivated Goal (get milk) was confronted with a Conflict (an armed robber) that forced a change in Goals (survive).

Regardless of the type of Conflict and the change it incites, a story isn’t worth telling if it works out exactly as everyone planned right from the beginning.

The Fine Line Between Decompressed Storytelling and Wasted Space

Let’s relate this topic to the fashionable trend in comics creation – decompressed storytelling – from an editing and writing perspective.

A typical single-issue Western comic has an average of 22 pages to get its story across, or at least the current chapter of the story arc. For that issue to keep a reader engaged and make forward progress on the plot, that single issue must be setting up the Conflict, directly in the throes of dealing with Conflict or experiencing the change that comes about from the Conflict’s resolution.

Keep in mind, a story is not limited to one Conflict. There can be several along the journey’s path; even several in a single issue.

Setting Up the Conflict

Setting up a Conflict is the number one area where most storytellers cross the line from decompression to wasted space. If we look at an all-too-familiar scene in modern comics, characters sitting around and chatting while eating, we see how it can be a worthwhile or worthless scene depending on how it’s handled. (We’re going to give Joe a break for a little while).

Sally is having Lunch with one of her best friends, June. They’re catching up on the current happenings in each other’s life and enjoying a light entree. Their talk veers into several topics that inform the reader about feelings and occurrences that affect each of them. The server brings them the check, and they leave.

— The End —

Although the reader is now well-informed about the lives of each character and the writer is confident this scene falls under the heading of “character development,” it’s very likely a complete waste of time. Why? Because expositional character development is worthless if it doesn’t plant the seeds for a coming conflict.

Here’s how that same scene could go differently and made invaluable to the story.

Sally is having Lunch with one of her best friends, June. They’re catching up on the current happenings in each other’s life and enjoying a light entree. Their talk veers into several topics that inform the reader about feelings and occurrences that affect each of them. Toward the end of their meal, the server brings them a desert tray containing mostly ice cream dishes to choose from. Sally politely informs the server that she’s deathly allergic to processed milk products and declines. They pay the check and leave.

–The End —

With that small nugget of information, the reader now knows Sally is in for a bad time if she mistakenly consumes something containing processed milk products. The writer can take evil glee in sending Sally to a blind tasting party where the night ends with Sally leaving on a stretcher or in a body bag.

This is one of an infinite number of scenarios where characters are sitting, talking, eating, or doing nothing particularly spectacular, but the scene becomes valuable because one or more seeds are planted to set up the coming conflict. In literary terms, this is commonly referred to as foreshadowing. A variation on this type of setup is Chekhov’s Gun.

“But, wait. How do I develop characters if they don’t get those quiet moments to breathe?” The answer is the classic “show don’t tell.” How your Character reacts to the Conflict, resolves it, and deals with the aftermath does more to inform the reader about your Character than 3 pages of dialog and thought balloons ever will.

Conversely, if you’re editing your work or somebody else’s, critically assess what looks like innocuous panels by asking “How does this set up the coming conflict?” If the answer is “It doesn’t,” cut it.

You only have 22 pages. Ruthlessly cut it.

In the Heat of Conflict

Everyone gets what a Conflict looks like… or do they?

In Western monthly comics, we tend to think of conflict as two costumed characters sparring for domination, but that’s not the whole story. Conflicts can be physical, emotional, and intellectual.

Physical Conflict

Back to our hapless friend Joe. His predicament is a classic physical Conflict.

Joe has a Motivated Goal defined by him getting from point A to point B. The robber is physically interfering with the completion of that Motivated Goal. This falls squarely in line with superhero battles you’d find in a typical Western monthly comic.

Emotional Conflict

A common example of an emotional conflict is the stereotypical lover’s spat. A couple arguing over a personal slight, rejection or misunderstanding is always bubbling with emotion. On the other side of their spat, the resolution may be enough to cause a split or for one of the two to take drastic action to fix the relationship.

Intellectual Conflict

Here we have the widest range of possibilities. An intellectual Conflict could involve two school professors debating how to cure a disease where the wrong outcome proves disastrous. An intellectual conflict could grow as large as two political factions debating over the appropriate fiscal policy. However it’s framed, the concept revolves around differences of belief and intellectual approach that inhibit moving forward.

Regardless of the type of Conflict, editorial culling is a must. Ask yourself “Does this page, panel, word balloon, or caption box build on the conflict currently taking place?” If the answer is a resounding “no,” cut it.

Cut it without mercy.

The Aftermath of Conflict

It’s all about the change. In literary terms, it’s the denouement. In less fancy terms, it’s the release and unraveling after the Conflict resolves, and the gravity of what happened sinks in with all involved.

If we go back to the original rewrite from Joe’s milk run, the aftermath is Joe’s realization of how the robbery affected him. What does he do with those feelings? How does he choose to move on?

Sometimes this fall in the story can itself be a setup for another Conflict. If you’re editing a story, look for the changes after resolution. Are they clear? Are they meaningful? If the characters and everything around them go back to the way things were at the beginning of the story, your writer botched the ending.

Get the writer to fix it, or find a better writer.

Final Thoughts

For any story to be considered complete, it must contain the basics: characters, actions, and a beginning, middle, and end, but without a Conflict to incite change, there is no story.

Without Conflict, you have nothing more than a well-structured description of events. Push your characters. Bend them, break them, set them up, and knock them down.

For writers and editors, always be asking how a scene sets up the Conflict, puts the Conflict on full display, or deals with the change brought on by the Conflict’s resolution. If it doesn’t, take it out.

Your reader will thank you for it.

Let us know what you think. Does Conflict make a story worthwhile or do you have a better opinion? Give us your best opinion down in the Comments, and please share this post on social media using the links below.

We hope you found this article interesting. Come back for more reviews, previews, and opinions on comics, and don’t forget to follow us on social media:

If you’re interested in reading more comics to see Conflict in action, remember to let your Local Comic Shop know to set a few issues aside for you. They would appreciate the call, and so would we.

Click here to find your Local Comic Shop: www.ComicShopLocator.com