Treat Characters Like People, Respect the Family Budget, And Go to the Mountain

The Young Adult (YA) market has blossomed into a billion-dollar industry, so it should be no surprise western comics publishers want to get in on a piece of that action. With dismal and dwindling sales in monthly superhero comics, the old business adage of “stagnation equals death” is naturally forcing publishers to find a foothold in other markets.

However, the efforts by large western publishers to crack the code of the YA market have largely fallen flat (Remember, DC Zoom? Neither does anyone else). But why? Why have the Big 2 (DC and Marvel), with millions in corporate backing and a lifetime’s worth of intellectual property that used to appeal to middle-grade readers, now come up short?

This article will look at the value of the YA market, what’s worked, what hasn’t, and what strategic points western comics publishers can consider to help crack the code.

Why Go After the YA Market?

Money and growth. It’s really not a complicated or mysterious question. All publishers everywhere need to grow to survive, and there’s a huge amount of financial potential in the middle-grade (about 12-18-years-old) demographic of readers.

Let’s take a look at some of the numbers that made the news rounds with good reason — Data is powerful.

According to a joint report between ICv2 and Comichron, 2019 “comics” sales topped $1 Billion dollars. The reason the word “comics” is in quotes is that every bit of published content that combines words with pictures is lumped together, not delineating between manga versus YA graphic novels versus monthly western superhero comics.

When you dig beneath the surface totals of the report, here’s the key takeaway according to the same ICv2 report:

Sales of kids graphic novels in the book channel, which includes chain bookstores, mass merchants, major online retailers, and Scholastic Book Fairs were once again driving the format.

Dig a little further and the sales of western monthly comics (DC, Marvel, Image, etc.) were almost entirely flat. There was little to no growth at all from the Big 2, and some publishers, such as IDW Publishing, dropped drastically. In short, the comics industry as a whole is growing, but the YA and manga winners are carrying the losers.

It may seem harsh to use the word “loser,” but the only way to resolve the problem is to look at it with a sober eye. You can’t get to where you want to go if you don’t know where you are.

Now that we know where the western publishers are, it’s easy to see why there’s a push to break into the YA market. Now, let’s look at why attempts to break in haven’t worked, and what adjustments could be made.

How Do Customers Buy YA Graphic Novels From Comics Publishers Today?

You might think: “What do you mean? They just go buy them. What does ‘how they buy’ have to do with anything?”

In a normal book-buying distribution model, you’d be right. A purchase is a purchase, but for reasons that will become very obvious, western comics publishers don’t take a typical approach to distribution.

Keep in mind, these are typical scenarios, but it’s not the end all be all. There are always exceptions.

Let’s say DC Comics publishes a graphic novel about a de-aged version of Clark Kent in High School but it’s categorically not Superboy or Smallville.

Scenario A

An older teen will go into a Local Comics Shop (LCS), see a shelf copy of the graphic novel. They leaf through it, decide it’s not for them because nothing about it looks like a familiar Clark Kent, and leaves with their weekly pull box contents.

Scenario B

A younger teen goes into an LCS while their parent is shopping in the grocery store across the street. The younger teen sees the graphic novel, leafs through it, maybe thinks about purchasing it, sees the $16.99 cover price, and puts it back to browse through other titles on the shelf.

Scenario C

A father who’s a lifelong comics fan goes into an LCS with his daughter. She browses through the shelves and picks up the graphic novel. She asks her father to buy it for her. The father leafs through it, confused by the contents because this version of Clark Kent is only similar to the traditional character of Clark Kent in name only. He sincerely says to her “That’s not the real Clark Kent. I don’t what that is, but let me show you something better.” He then proceeds to show his daughter a back-issue collection of Superboy from the Bronze Age of comics (1970-1983).

Scenario D

An adult is shopping in the few remaining chain bookstores for a gift for their child’s birthday. They head over to the YA section and see large displays for Dog Man by Dav Pilkey. The covers look cute and fun, so they pick one they’re sure their child doesn’t have and buys it. The Clark Kent graphic novel is high up on a shelf in the corner gathering dust, wedged between copies of the All-Star Superman trade and Superman: The Death of Superman trade.

There are a plethora of other scenarios but these four highlight the fundamental issues. Getting YA content from the western comics publishers into the hands of young adults that want them is a struggle. Getting them and keeping them coming back for more is hindered by three big factors — content, price, and placement.

What’s Wrong With the Content?

This point is probably complex enough to warrant its own article, but the crux is taking something that works for one market and trying to turn it into something else for a different market.

Let’s get this crystal clear. Different markets like different things. That point is self-evident because if everyone liked everything, there would be no concept of markets.

If a motorcycle dealer takes a Harley Davidson chopper, paints it bright pink, applies flower decals on the gas tank, and puts bicycle tassels on the handlebars, it won’t become the must-have purchase for a 14-year-old girl that wants a new bike for Christmas.

If McFarlane Toys puts out an open call for new figurine ideas for the Spawn collection, it’s a sure bet they’re not going to pursue a contract for My Little Pony variants.

Get the picture? Successful products that have endured appeal to a specific cross-sectional market of buyers.

When we take this back to western superhero comics, Superman is an established character with a long history. Superman fans like Superman for he is and what he represents. When you take Superman and change him into something he’s not to appeal to a different market, existing fans reject it. The new market may recognize the YA version of Clark Kent but nothing of what made the character popular in the first place is present, so the new market passes it by.

Characters Are Not Brands

We see this mistake happening over and over because publishers increasingly treat these characters as brands. A brand is something that can be slapped on any product with the expectation fans will buy it no matter what. But in reality, the characters are not brands within their own medium.

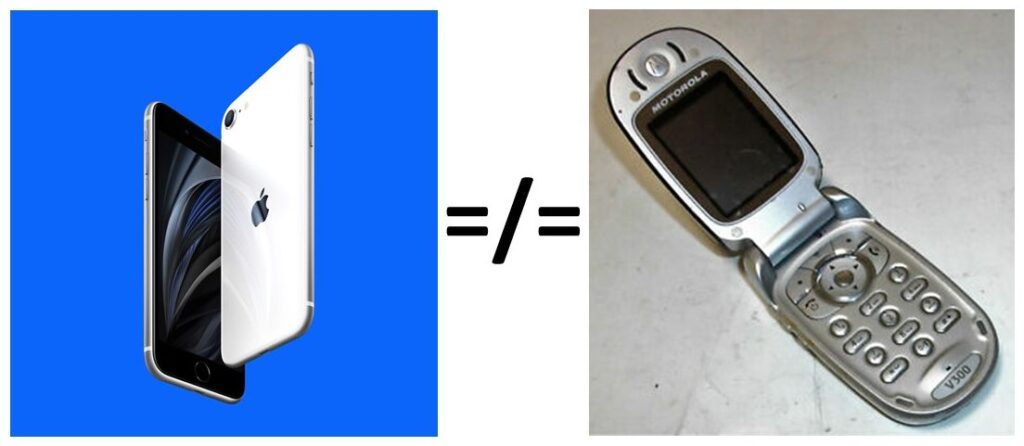

Let’s look at a high-profile example: the iPhone. The iPhone is arguably the highest selling and most prestigious product Apple makes, but the iPhone is not the brand. Apple is the brand.

From a marketing perspective, Apple stands for luxury consumer gadgets. Put an Apple logo on a Motorola phone, it will carry a certain amount of reputational expectations. Put an iPhone picture on a Motorola phone, and it won’t make much sense.

IPhone customers reject the Motorola outright as not a “real iPhone,” and customers vaguely aware of iPhones only care about a good smartphone. A new customer won’t buy it if it’s made with cheap plastic and gets lousy reception. Do you see the disconnect?

Brands only matter to existing customers.

The iPhone analogy is, admittedly, silly but the logic still holds for superhero publications. It’s a common practice to find a lunchbox or bed sheets or T-Shirts with Batman’s symbol on it. Outside the medium of publishing, you can get away with symbols and logos. Putting the Bat-logo on a YA book doesn’t have the same effect because readers will want a Batman story. If they don’t get one, the book will fail.

The publisher is the brand. Characters are not brands. They are a specific product that appeals to a specific market. Twisting and turning them inside out won’t magically make them attractive to a different market.

What’s Wrong With the Price?

Let’s take a step back and think about the target market — 12-18-year-olds.

They’re in school, likely don’t have jobs or a steady stream of disposable income. Therefore, the money to pay for a YA graphic novel comes from their parents. Parents with school-aged children have lots and lots of bills, including clothes, food, and school supplies.

Given the choice between a 286-page, hardcover edition of Dog Man: A Tale of Two Kitties retailing for $4.84 and a 208-page, paperback edition of Gotham High retailing for $12.99, the choice is clear.

The Dog Man title is bigger, a proven title that’s school-approved since it’s distributed through Scholastic, and it’s cheaper. Gotham High is smaller, resembles nothing that anyone recognizes, may or may not have YA-friendly content, and it’s more expensive.

If publishers want YA market share, they need to adjust pricing to match the YA market’s budget and make parents feel like it’s money well-spent.

What’s Wrong With Placement?

As the saying goes: ‘If the mountain will not come to Muhammad, then Muhammad must go to the mountain.‘

The western comic market has a very heavy reliance on the LCS network for endpoint distribution, and as the scenarios laid out above point out, the YA market generally doesn’t hang out in the LCS. We know this from data such as this 2017 ICv2 report on comic purchasing demographics:

72% of purchases in comic shops are by men, with 30-50-year-olds the largest age category

Scholastic is crushing, metaphorically speaking, the big comics publishers in the YA market because they go where the kids go — schools, community centers, libraries. They don’t wait for the kids to come to them.

As long as the LCS network keeps the publisher’s product isolated to the store’s foot traffic, there’s no chance of competing against the likes of Scholastic.

How Do We Fix It?

If the primary problems are content, price, and placement, then the areas to tackle first are content, price, and placement. Content is the more complex of the three, so let’s quickly address the other two.

Lower Cover Prices to Match The YA Market’s Budget

Again, this is not complicated. Look at the average spending habits of school-aged children within book drives at middle and high schools.

The graphic below comes from the School Library Journal to help librarians budget for new book purchases. The average Scholastic book fair will price the same books lower for greater volume sales and a percentage of the fair’s proceeds go back to the school.

Publishers, these are the price points you must beat by at least 30% to compete.

Put The Books Where the YA Market Can See Them

Go to the mountain, Muhammad.

Again, we rely on research and follow the example of those who are successful. Scholastic gets sales because they are deeply entrenched in the school systems of North America through school boards, teachers’ unions, and the local PTA. If an organization has something to do with running a school, Scholastic is there.

Publishers, find a way to get in front of school administrations. It won’t be easy. Scholastic won’t want to share their piece of the pie, but that’s the mountain Muhammad must climb.

However, there is another approach made apparent with plain, simple research. We look to Pew, the gold standard of analytics and research data, and ask the basic question: “Where do teenagers hang out?”

According to a 2015 Pew research study:

Fully 55% of teens spend time with their closest friend online on a regular basis, which is similar to the share of teens who spend time with close friends at someone’s house. Teenage boys are especially likely to spend time online with close friends, as 62% do so regularly, compared with 48% of teen girls…

Roughly one-quarter (23%) of teens regularly spend time with their closest friend at a coffee shop, mall or store. Girls are twice as likely as boys to hang out at these places: 30% of teen girls regularly spend time with their closest friend at a coffee shop, mall or store, compared with only 16% of boys.

As the data suggests, kids are hanging out online most of the time. And the ones that do hang out in person do so at casual stores such as coffee shops and the mall. The days of the newsstand may be over, but a strategically placed set of graphic novels at the local Starbucks or online ads targeted at those online hangouts may be worth a trial run or two.

Food for thought.

Find Out What Content Kids Like And Publish It

Taking a quick run at content, should the publishers de-age their superheroes into a YA title? No, absolutely not. It doesn’t work. We know it doesn’t work because the data tells us so.

The graphic above was taken from the ICv2 report in collaboration with NPD Bookscan based on the only metric that truly counts — Sales. Notice there’s not a single DC, Marvel, IDW, or any other recognizable comics publisher in the bunch.

The point here is the biggest publishers aren’t able to crack the Top 20 in the YA Market for a very fundamental reason. They’re not making content kids want, which means there’s a disconnect between what comics publishers think kids want and what kids actually want.

Ideally, publishers shouldn’t write a single script or draw a single panel until they do one thing first — talk to kids and find out what they like. Ask the questions. Why do kids like Dog Man so much? What makes Guts such a success?

Do the research, ask the questions, and the answers will likely sound very familiar. Stories about kids with relatable, age-appropriate personalities and relatable families going through interesting challenges.

Conversely, grim and gritty teenaged billionaire Bruce Wayne is probably not going to resonate with the average 13-year-old. A stunningly beautiful Amazonian princess struggling to find a date for the Junior High prom doesn’t quite have that ring of authenticity. And it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense to read about High School freshman Tony Stark having to put up with the class bully.

Characters are not brands.

Make new characters. Make them age-appropriate and relatable, in both personality and their relationships. Then layer the superheroics on top.

Final Thoughts

The YA market is a vast and fertile field of new readers for western comics publishers. It’s worth pursuing, but so far, attempts have largely fallen flat.

To crack the code of getting into the YA market, look at the areas where the biggest players like Scholastic succeed and beat them at their own game in terms of content, price, and placement.

- Do make new, relatable, age-appropriate characters with relatable relationships.

- Do price YA books with parents’ budgets in mind. Pricing geared towards adult males with disposable income is a non-starter.

- Do put the comics, trades, and graphic novels in front of kids where they are, not where you want them to be.

Starting with these few, strategic changes, the possibility of gaining a piece of the YA market will at least get significantly higher.

We hope you found this article interesting. Come back for more reviews, previews, and opinions on comics, and don’t forget to follow us on social media:

If you’re interested in reading comics, remember to let your Local Comic Shop know to find interesting titles for you. They would appreciate the call, and so would we.

Click here to find your Local Comic Shop: www.ComicShopLocator.com