No, comics have not always been political, or at least, not in the way that most people think about politics. There’s a common misconception that everything everyone does is a political act. That misconception has a historical foundation; one which this article will clarify. In the case of comics, the issue isn’t whether or not politics have always been there. The issue is a lack of definition for the philosophies that motivate every character in their own story.

This article will define the core philosophies that drive superhero comics characters, clarify the distinction between philosophy and politics, and lay out a path for modern superhero comics to tell better stories.

Where Did This Argument Come From?

There’s no single starting point for individuals arguing about politics in comics, however, the common example often pointed to is a classic Captain America cover depicting Captain America punching Adolf Hitler. For all the attention this cover gets, the depicted fight scene and everything surrounding it doesn’t appear in the comic. The cover is a misleading piece of pro-war propaganda commonly distributed before and during World War II.

Since the actions depicted on that cover don’t appear in the contents of the comic itself, the amount of attention paid to that cover speaks to the power of propaganda and not to the content of Captain America’s character. This is not the first example of an individual cover, page, or panel taken out of context to serve as justification for a broader argument. However, one cover does not make a character.

Defining A Character

The characters that survive and thrive beyond their first few issues are characters that are part of a memorable story and are relatable to the reader in an emotional way. Emotion is the key to relatability (we’ll define why a little later). When readers make an emotional connection with a hero’s journey, the likelihood that character will hold a memorable place in the reader’s mind is significantly higher.

A Necessary Brief on Human Behavior

This part is going to be dry but it helps to understand how we make the case for philosophy versus politics in the rest of the article. I promise it’ll go quickly.

Readers can relate to a character only when the character speaks, acts, and makes decisions that feel natural to how humans behave. There are many different psychological and behavioral models for understanding how humans react in any given situation, but they all share a common set of descriptors. One of the most common models we’ll use for this article is known as the TFAR model.

T stands for thoughts. Everything a human consciously says or does first starts with a thought. There is no exception. The thought comes first.

F stands for feelings. Feelings always follow a thought. It’s the emotional reaction to a memory or situation that person might be in. Feelings are what motivate us to take action.

A stands for actions. Humans are spurred on to take action when motivated by their feelings. We never act simply because we can. We act to achieve some goal.

R stands for results. The outcomes of our actions in life stem from the actions we take, both in word and deed. Even doing nothing is a conscious action to let external factors play out toward some result.

That’s it. Not so bad, right?

Remember: Thoughts generate Feelings. Feelings motivate Actions. Actions produce Results.

What Does This Have To Do With Superheroes?

We can relate to and understand characters in superhero comics if we understand, first, the thoughts they have, the feelings generated by those thoughts, and the understandable action that follows. When a character’s cycle of behavior lines up, we can sympathize (maybe even empathize) with that character to share in their experience.

Conversely, if we don’t understand why a character is saying what they’re saying or taking the actions they’re taking, it’s very difficult to relate to them. That character will come off as chaotic or unnatural.

Here’s the kicker. The set of rules that dictate a character’s actions – what they will or won’t do – is encapsulated in that character’s personal philosophy. For example, Batman’s “No Kill” rule is part of Batman’s personal philosophy. It’s not a political stance, and it’s not a part of a political belief system. It’s his moral compass. That compass guides his actions during whatever challenge he faces and is uniquely specific to him. And, that compass is built on the Bruce Wayne’s thoughts about an event (his parent’s death) followed by the feelings that memory instills in him (grief, regret, anger, etc.).

The Difference Between Personal Philosophy and Personal Politics

Unfortunately, too many pundits, analysts, and opinion-makers have adopted a view that says politics and philosophy are interchangeable. There is a historical starting point for how these concepts became intertwined (again, more on the history in a little bit), but it is still a conflation. Too often in this soundbite-obsessed, social media culture, the distinction between the two becomes very muddy.

Per Merriam-Webster, politics is defined as “activities that relate to influencing the actions and policies of a government or getting and keeping power in a government.”

The definition isn’t muddy, complicated, or hard to understand. Politics surrounds the influence and change of government. That’s it.

Personal philosophy is entirely focused on the individual, their life experience, and how those thoughts and feelings guide the course of their life. Politics is relates exclusively to changing government.

Why Do People Confuse Personal Philosophy With Politics?

Bad takes over time contribute to this misunderstanding, but there is a common historical source, starting with the phrase: “The Personal Is Political”

The phrase “the personal is political” is commonly attributed to self-described feminist writer, Carol Hanisch, in her essay of the same name published in 1970. The essay explores the ideas of political action during the second-wave feminism movement. Ideas focused on women’s issues and rights from power dynamics in the home and the workplace. A quick way to define the phrase’s meaning is “women’s personal issues (e.g sex, childcare and the idea of women not being content with their lives at home) are all political issues that need political intervention to generate change”.

In other words, the writer’s intention behind the phrase “the personal is political” is that governmental change is required to bring about improvement for personal issues shared by a cross-section of women. It’s interesting to note Hanisch has since disavowed coining the phrase.

With clarity about the origins of the phrase and its continuation in Western culture, we can draw a reasonable conclusion around why personal philosophy and politics are viewed by some as interchangeable. This overly-simple phrase, meant to address specific circumstances, has been used and re-used for decades with increasingly broader applications, even when it doesn’t make sense. “The personal is political” phrase has been co-opted and spread around by people who don’t understand its meaning or origins and adopted as a mantra, incorrectly applied to all areas of life.

How did this happen? How ideas propagate is never certain but a reasonable guess would be a combination of word of mouth and indoctrination through the University educational system.

For example, a staunch feminist professor teaches “the personal is political” mantra to students to emphasize the need for political action to effect personal change. Students hear the mantra without clearly grasping the meaning or intent and assume the professor is simplistically saying that all politics is influenced by personal action, therefore, all action is political. If all action is political, then every action a superhero takes is political. Therefore, politics have always been in comics.

It’s the Transitive Property of Ignorance.

Knowing this, we can now show how enduring superhero characters survive and thrive because they adhere to a personal philosophy; not a political one.

The Personal Philosophy Of Superheroes

Let’s take two well-known characters: Batman and Superman. They both have a nearly identical set of philosophies that could be simplistically defined by two rules:

- Protect and save the innocent

- Do not kill

Nearly every superhero has the same set of core philosophical beliefs. There are exceptions such as Wolverine and Deadpool who kill as an acceptable means to an end, but they’re both considered heroes because they minimally adhere to rule #1. It’s interesting to note Marvel’s roster of characters has a greater percentage of heroes who kill compared to DC’s.

Superman will use his superior strength and abilities to contain an armed bank robber by simply snatching up that criminal and dropping him off at the nearest police station. He can stop a crime and effect an arrest very quickly without anyone getting hurt or killed.

Batman does not have the luxury of Superman’s powers, so he may accomplish the same task with the same set of philosophies, but his actions require beating up the armed bank robber, breaking several bones in the process. The criminal may be harmed but he’s not killed, and Batman fulfills his mission by saving and protecting the innocent. Batman and Superman take very different actions to achieve the same results, but their core philosophies are almost identical.

Again, philosophy is the set of rules a character will follow based on their thoughts and feelings.

By contrast, nothing about what Superman and Batman are thinking, feeling, or doing is meant to effect political change; meaning governmental policy. Quite the opposite, their actions typically operate outside the rules of government, resulting in the assigned title of “vigilante.” By definition, a vigilante is an individual who acts outside of the law and sometimes in direct opposition to it. Not only are Batman and Superman’s actions not political, but their actions are almost entirely in opposition to or outside of politics.

You could also argue that characters most prone to “always being political” are villains. E.g. Lex Luthor, Maxwell Lord, Wilson Fisk, and so on.

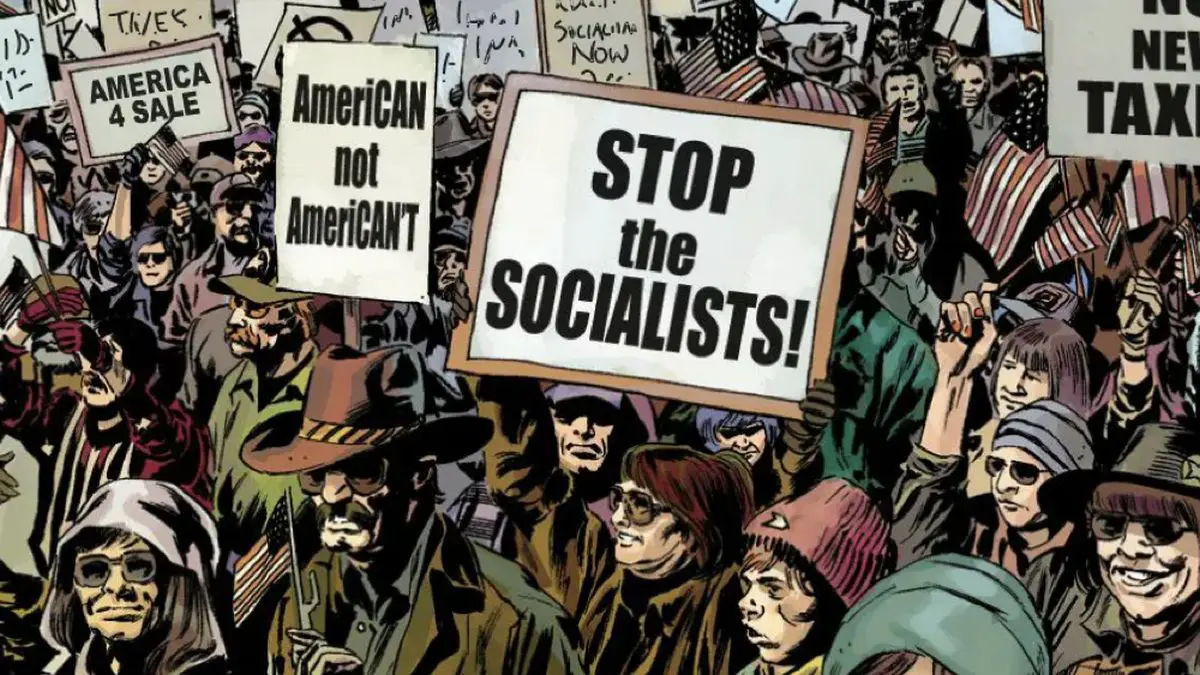

When Politics Comes First, Characters Fail

Increasingly, there are examples of newer characters aggressively marketed by mainstream Comics Publishers through popularity and gimmickry. However, these characters struggle with mainstream acceptance and are unable to stand on their own within comics (reflected by low sales) because they were created with politics in mind first.

Looking back to the TFAR model, creators that start with a political agenda in mind implicitly begin with their character’s actions (e.g. representation or social activism) before defining the thoughts and feelings that motivate the character. Without a solid foundation of a personal philosophy, the reader won’t understand what motivates the character’s actions and the character loses relatability. The character, in effect, becomes a hollow mouthpiece for the creator and not a fully realized character.

The Harley Quinn Problem

Harley Quinn was created as a sidekick/girlfriend for the Joker. She immediately gained popularity because her existence was defined by a toxic relationship. Consequently, readers could relate to the circumstance Harley found herself in and the feelings Harley would experience as a result, but the thoughts and feelings Harley developed were squarely grounded on enduring her relationship with Joker, and later, getting out of that relationship.

Now, Harley Quinn is almost completely untethered from her relationship with the Joker. Without the thoughts and feelings associated with her toxic relationship, a writer has yet to undertake the steps to define what new thoughts and feelings drive Harley to move forward without the Joker. In other words, Harley’s personal philosophy was originally intrinsic to the Joker’s presence in her life. Without the Joker, Harley has no personal philosophy and, therefore, no direction. Harley is floundering.

Do the sales and storylines reflect a lack of direction for Harley? Yes. As of this writing, Harley has two solo titles out and supporting appearances in several other titles. January 2022 rankings show neither of Harley’s solo titles made it into the Top 25 metric within DC’s sales alone or across Western publishers as a collective.

You can see this pattern across newer characters in both Marvel and DC. New characters or characters that have been rebooted with a socio-political goal in mind are all struggling, including (aged up) Jon Kent, Naomi, Children of the Atom, Teen Lantern, and more.

To be clear, it’s not the desire to take political action that harms a character’s growth. The harm comes from starting with the political action first without taking the time to firmly establish the character’s thoughts and feelings to motivate their political actions.

How To Respond To The “Comics Have Always Been Political” Argument

The easiest response is to send them this article. 😉

That said, you may only have a few minutes of conversation, and all you can do is relay a summary. Keep it clear. Keep it simple.

Start with explaining how humans relate through Thoughts, Feelings, Actions, and Results. In that order.

Explain the source of “the personal is political” mantra and how it’s been incorrectly applied over decades.

Use the example of Batman and Superman fighting crime as an example of personal philosophy in action in direct opposition to politics. Feel free to add in that characters who most often engage in active politics tend to be villains.

Concede that there’s nothing wrong with a character taking political action as long as the personal philosophy behind it is clearly defined first.

Building A Better Hero

Armed with this information, and seeing how some characters work when others don’t, we can write better characters.

In a first appearance issue or origin issue, the first step is to quickly define what the character believes in and why they believe it. It could be through their upbringing, a tragedy they endure, a unique life event, or an accident of fate. Whatever the reason, readers must be able to see very quickly and easily what that character thinks and feels so that they can understand their motivations.

The reader doesn’t have to agree with the character’s motivations, but the reader must at least be able to understand them. Every discussion, every action scene, every life choice a character makes should tie back to their personal philosophy.

In addition, when a writer is tasked with writing stories for an established character – for example, Batman – it is the writer’s responsibility to make sure every bit of dialogue and every action taken by Batman is in line with his moral compass. Good writers will not see this point as restrictive but as a helpful guidepost to make sure the character is consistent with their origins.

Conclusion

The purpose of this article was to answer a divisive question – Have comics always been political? The short answer is “no”.

It’s more accurate to say characters who have endured for decades have clearly defined personal philosophies. Some readers and creators conflate politics with personal philosophy due to a misunderstanding of the “the personal is political” mantra, and while a character’s actions are always personal, they’re not always political.

When the distinction between personal philosophy and politics is clarified, new characters are written better, existing characters are written consistently, and the character’s actions are relatable to the reading audience.

We hope you found this article interesting. Come back for more reviews, previews, and opinions on comics, and don’t forget to follow us on social media:

If you’re interested in this creator’s works, remember to let your Local Comic Shop know to find more of their work for you. They would appreciate the call, and so would we.

Click here to find your Local Comic Shop: www.ComicShopLocator.com